American slavery began when wealthy Southern aristocrats replaced their indentured servants with African slaves, held in perpetual bondage for generations. When the Constitution was written in 1787, with a significant portion of its authors slave owners themselves, several concessions were made to the slaveholding South. Most infamous of these was the three-fifths clause, which counted 60% of the state’s enslaved (and disenfranchised) population when determining representation in the House of Representatives, granting the Southern states disproportionate political power.

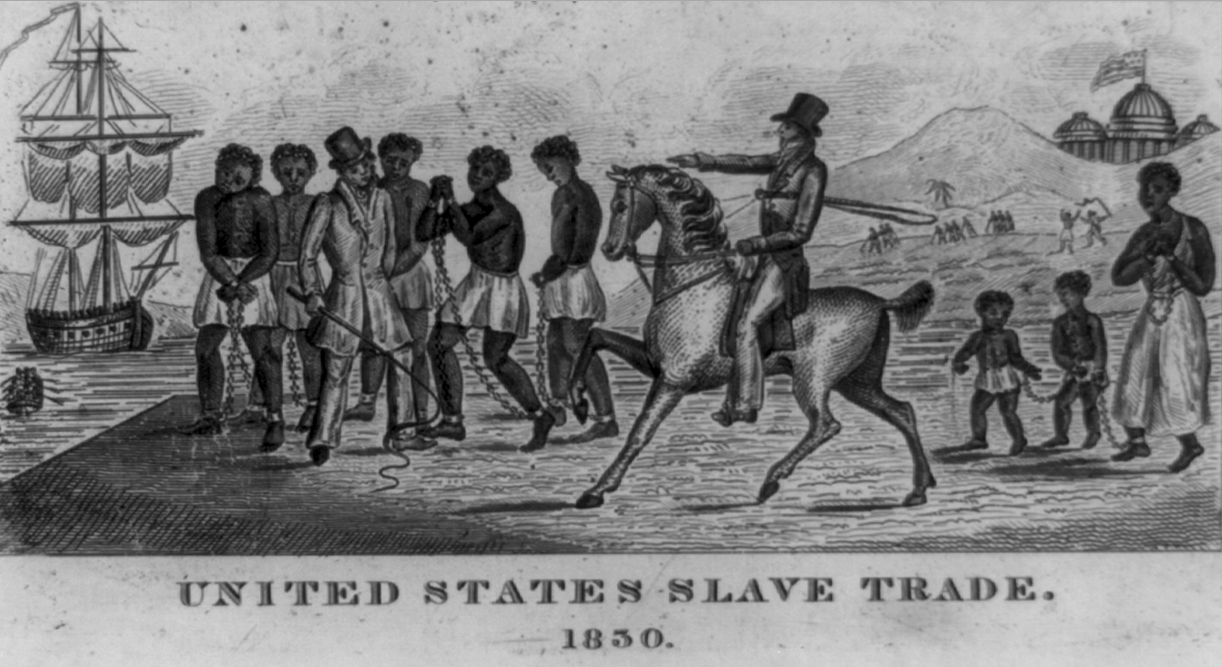

The overseas slave trade was outlawed in 1808, but trade of slaves between states flourished. The enslaved population increased by about 65% between 1790 and 1830, reaching 2,000,000.

“[Female slaves] must be entirely subservient to the will of their owner, on pain of being whipped…quite to death, if it suit his pleasure. Those who know human nature would be able to conjecture the unavoidable result, even if it were not betrayed by the amount of mixed population.” — Lydia Maria Child, An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans, 1833.

United States Slave Trade, engraving, 1830. [Courtesy of the Library of Congress.]